Good morning everyone! In 2021, Dr.Charmaine Nelson contributed this eye-opening and informative piece, and today, the International Day of Remembrance of the Slave Trade and its Abolition, I thought it would be important to reshare this piece. Dr. Charmaine A. Nelson, a professor of Art History and the Tier I Canada Research Chair in Transatlantic Black Diasporic Art and Community Engagement at NSCAD University, is all about the history of Transatlantic Slavery.

Take it away, Dr. Charmaine!

Canadians know next to nothing about our history of Transatlantic Slavery. This fact should not be surprising since our educational system – kindergarten to university – provides little to no opportunities to learn about this essential global history. Those of us who spent our school years in Canada know well what content gets delivered instead. As a writer, a day away from Black History Month (African History Month), well-intentioned elementary and high school teachers across the nation are preparing content on the Underground Railroad. But in choosing to teach about a history spanning approximately 30 years (from the end of slavery in the British Empire in 1834 – meaning here at home too – to the end of the American Civil War in 1865), we have retroactively transformed ourselves into the anti-slavery heroes who saved enslaved African Americans from the deadly machine of plantation slavery in the American South.

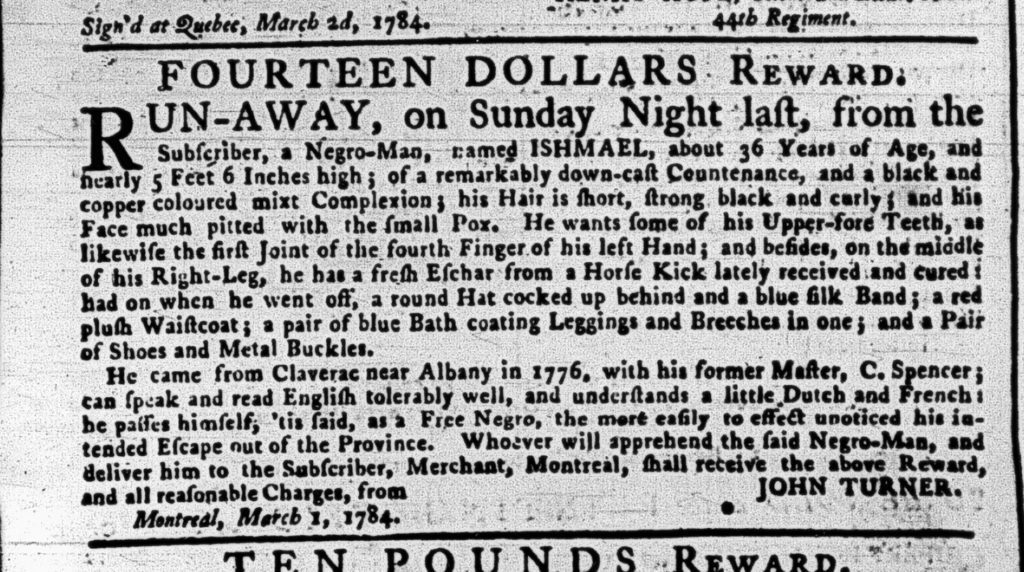

While the Underground Railroad was a stunning achievement in collective resistance and allyship, it was also a mere fraction of the 200-year history of Canadian Slavery, the period when we were also the “bad guys”. Furthermore, what no one wishes to remember is that prior to 1834, enslaved people in Canada routinely ran southward, not in search of a free state, but simply to get as far away as possible from their Canadian slave owners. Therefore, when the white Montreal slave owner John Turner Senior printed a fugitive slave advertisement on 11 March 1784 in the Quebec Gazette to recapture “a Negro-Man, named ISHMAEL,” his ad included Ishmael’s previous residence as Claverac near Albany, New York. (fig. 1) Clearly, Turner understood that Ishmael may have been fleeing southward to the US to reunite with the kin and community from whom he had been so callously separated.

As a person who researches and teaches Transatlantic Slavery, I am all too aware of how its legacies continue to haunt us today. The institutionalized anti-black racism that mars our corporate, economic, healthcare, housing, policing, and political sectors (to name a few) did not spring fully formed from the ground in the twenty-first century. Rather, this racism is simply a legacy of a centuries-long practice that has never been fully undone, redressed or atoned for. My new position as the Tier I Canada Research Chair in Transatlantic Black Diasporic Art and Community Engagement at NSCAD University in Halifax has placed me in the privileged position to build a research institute of my choosing. The Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery is the first of its kind in Canada and the world.

The decision to build a research centre that focuses on these complex and difficult histories was an easy choice for me. Born and raised in Canada, it was the critical alternative education of my home (a loving place with two Jamaican-born parents), that allowed me to identify the gaps, omissions (and quite frankly), the lies which riddled my elementary and high school education. Now seven books and over 250 speaking engagements later – most of which have focused on some aspect of the art and visual culture that emerged from the 400-year history of Transatlantic Slavery – I am continually confronted by the pervasive Canadian ignorance of our participation in the “peculiar institution,” as slavery was known.

Transatlantic Slavery was uniquely horrific. A race-based form of chattel slavery, it reduced human beings to chattel or moveable personal property, making them no different from everyday objects like a cart, desk, or bag of salt under colonial law. Deliberately organized in a matrilineal order, it incentivized rape and sexual coercion because any child born to an enslaved female (regardless of the race or social status of the father) immediately took on the status of the mother. While Indigenous people were sometimes enslaved, the only group that was always deemed to be “enslaveable” were black Africans.

Although many of us have watched American films about slavery (usually set in the deep south) like Gone with the Wind (1939), or more recently Django Unchained (2012) and 12 Years a Slave (2013), there are no comparable big or small screen, narrative or documentary films about Canadian Slavery. Instead, when Brad Pitt shows up as the carpenter named Bass at the end of 12 Years a Slave, it is as the white Canadian hero who gets word of Solomon Northup’s (played by Chiwetel Ejiofor) abduction and unjust enslavement in the south to his family and friends back north. Bass, the “good Canadian,” becomes Northup’s ticket to freedom.

Our non-existent Canadian Slavery curriculum and lack of popular cultural alternatives has also resulted in a pervasive ignorance about black Canadians. For starters, Canadian unfamiliarity with the fact that black people have been in Canada since the 1600’s leads to the pervasive misidentification of black Canadians as recent immigrants. Meanwhile, although the term “black” is usefully deployed as a catchall to describe the various people of African descent who were historically enslaved in Canada, it also occludes the knowledge of the extraordinary diversity of this group. But the advertising that emerged from slavery – here and abroad – can help to redress this blindness.

Black populations in Canada during the period of slavery were extremely diverse. One source which sheds light on this heterogeneity is fugitive slave advertisements. Also known as runaway slave advertisements, these notices were placed by white Canadian slave owners in order to hunt and recapture the enslaved people who resisted through flight. As one might guess, the ads documented the enslaved in invasive detail, providing descriptions not only of names, but of height, body type, hair style and colour, racial types, complexion, clothing, and even mannerisms. But significantly, details of a person’s location of birth, previous place of residence, accent, and languages were also routinely provided. This last group of identifiers were all things which worked to inform the ad’s readers about where the enslaved fugitive had come from and, significantly, where they might have been headed.

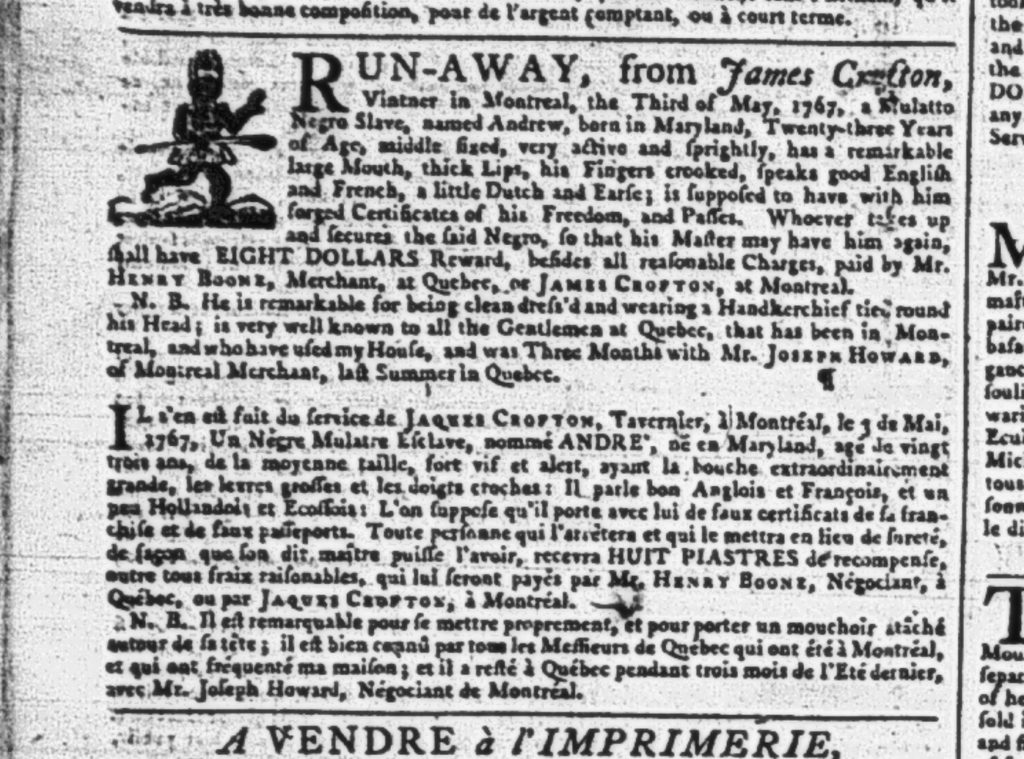

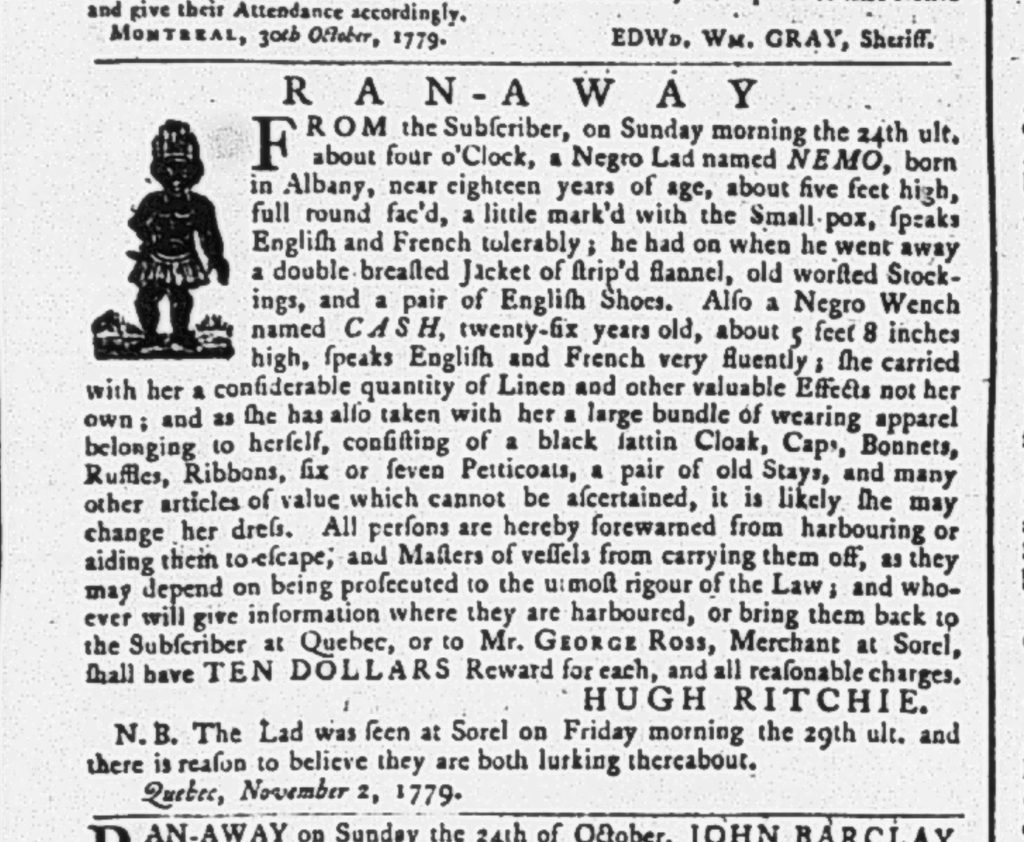

Several cases from the province of Quebec highlight these practices. An enslaved man named Andrew was described in a fugitive notice from 1767 as “born in Maryland,” while several years later in 1779, a “Negro Lad” named Nemo was listed by the Quebec City tailor Hugh Ritchie as having been born in Albany, New York. (figs. 2 & 3) Black people were also born into slavery Canada. Such appears to be the case with another of the people that Hugh Ritchie enslaved, the twenty-six-year-old Cash, who was described as a “Negro Wench”. (fig. 3) While Ritchie’s ad did not explicitly state Cash’s origins, his description of her linguistic abilities as “speaks English and French very fluently,” indicates that she was likely born in Quebec where, unlike other Canadian provinces and various parts of the US, both languages were commonly spoken.

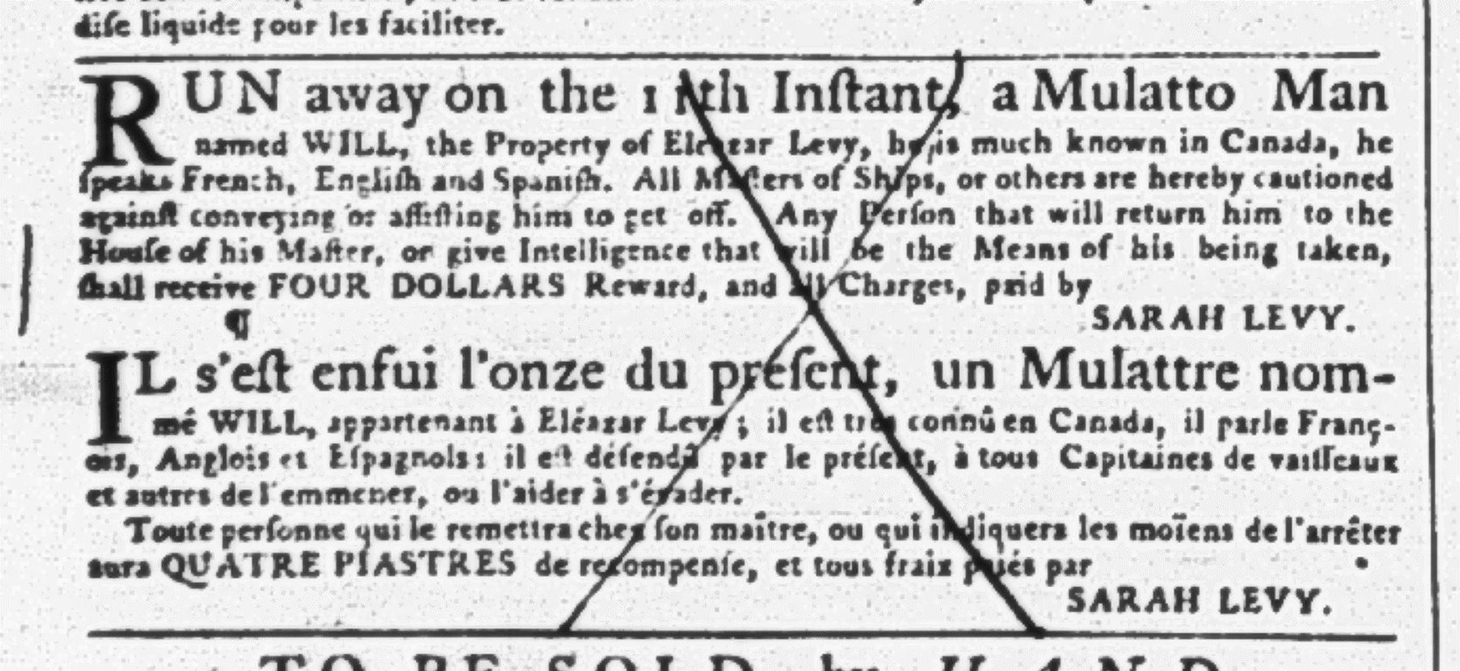

Enslaved black people were also forcibly shipped to Canada from the Caribbean (English and French controlled islands) by West Indian Merchants like James McGill of Montreal and Joshua Mauger of Halifax. Evidence of these Canadian-Caribbean trade routes appears in another fugitive notice posted in the Quebec Gazette in 1779 for the return of JNo. Thompson who was described by Simon Fraser as “a black Boy…born in Spanish-Town, Jamaica” who had escaped from the ship Susannah. (fig. 4) Although colonial trade was normally limited to traffic within each empire (meaning for Canada, from other British or French territories), these notices even hint at the presence of black people from outside of these colonies. Placed on 15 July 1768, Sarah Levy described a runaway “Mulatto Man named WILL,” as speaking “French, English and Spanish,” the last language, decidedly uncommon in the region. (fig. 5) Will then, had likely been born in a region where Spanish was spoken – like Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico or Mexico – or spent a significant period in the household of a slave owner who had spoken the language.

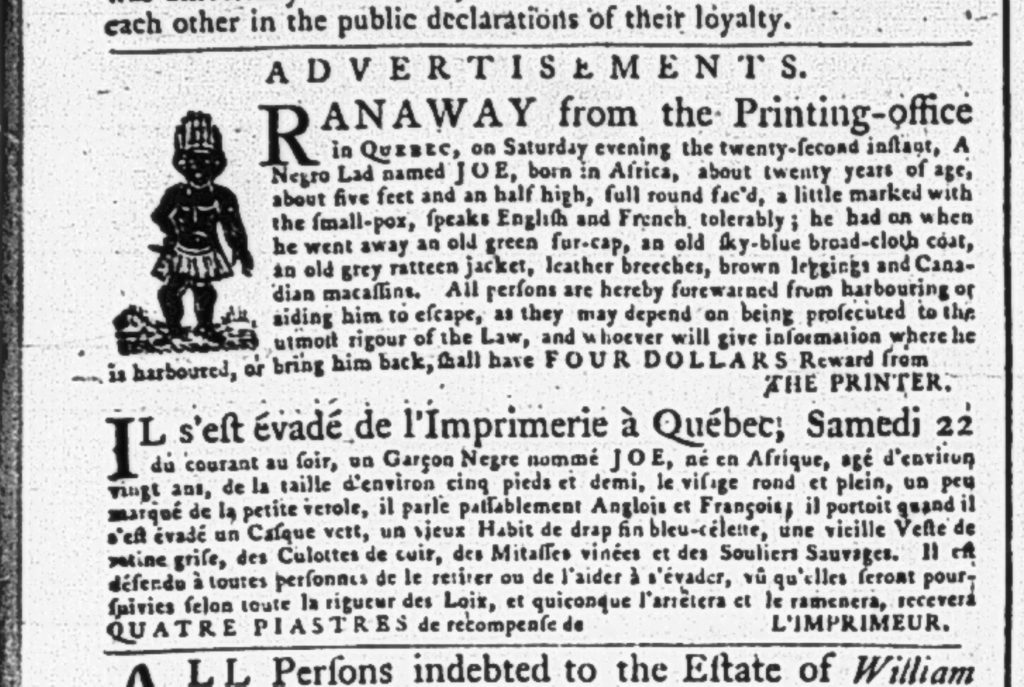

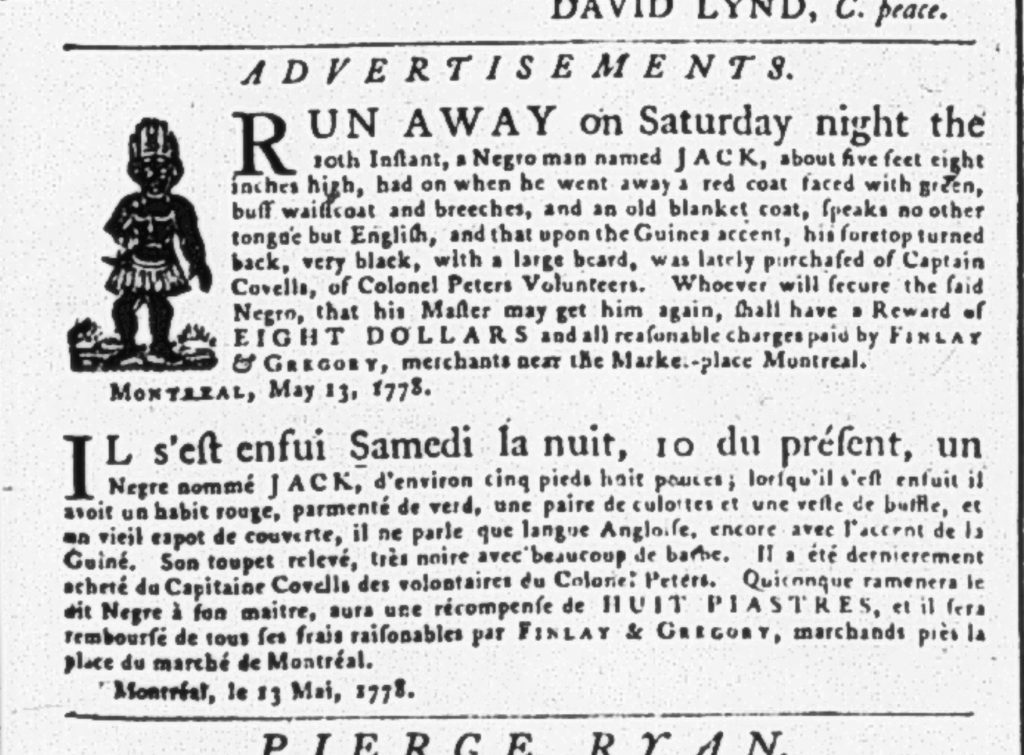

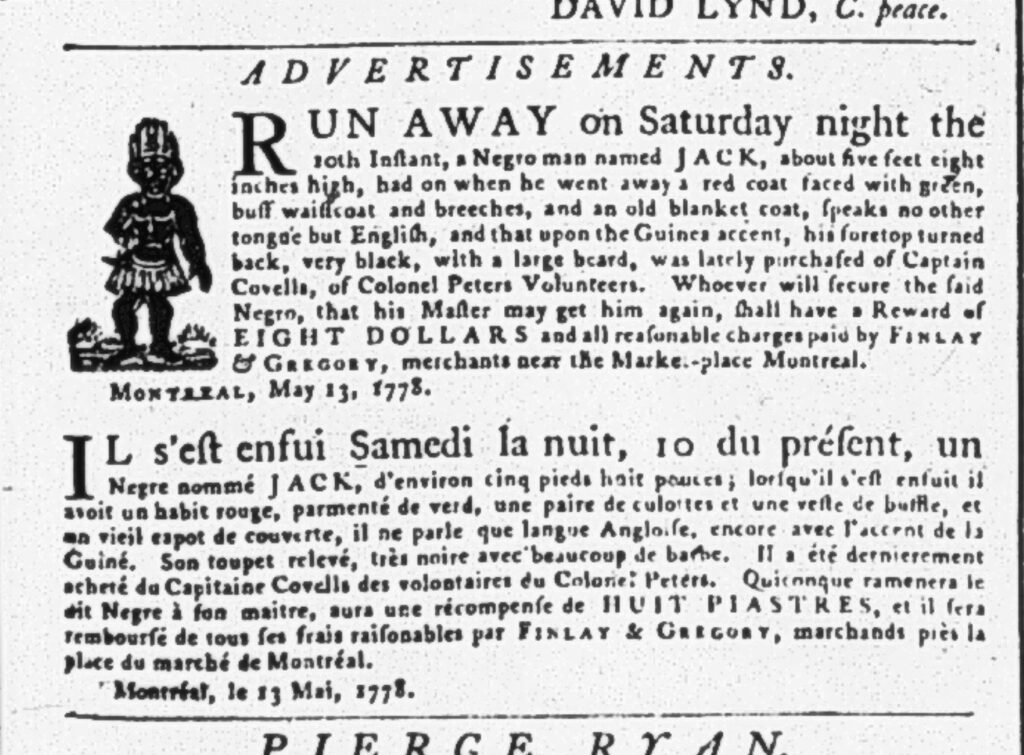

But the smallest group of enslaved blacks in Canada was those born on the African continent. Unlike slave owners in tropical locales who routinely dealt with slave ship arrivals directly from the continent (and therefore African-born captives of various ethnicities), Canadian slave owners had little to no familiarity with African-born people. Slave ships did not arrive in Canada directly from Africa. Therefore, while slave notices from places like Jamaica routinely named the ethnicity of escaping African-born people in fugitive advertisements (ie. Congo, Coromantee etc.), Canadian notices used more generic terms like “African-born” or “Guinea accent”. (figs. 6 & 7)

Given this evidence, at a minimum, blackness in the period of Canadian Slavery meant: African Canadian, African American, African Caribbean (Anglo- and Franco-), and African-born people; a diversity that continues to grow today. This extraordinary diversity meant that black people would not have necessarily shared a common language, never mind spiritual, clothing, hair, food, music, or kinship practices. But forced into alliance by the brutality of slavery, they came to create common rituals, dialects, and cultures to survive. With the under-funded and neglected state of Canadian Slavery Studies, scholars have yet to explore any of these dimensions of Canadian slave life in depth.

Understanding the complex diversity of blackness in the period of Canadian Slavery is a defense against one of the most routine mechanisms of racial oppression, the stereotypical belief that all black people are the same. Recognizing the 200-year history of slavery in Canada presupposes an acknowledgement that enslaved and free black people have lived in Canada since the 1600’s. By acknowledging Canadian Slavery, we move towards debunking the myth of the ideal Canadian citizen as only white and allow black Canadians to be more than perpetual immigrants.

Dr. Charmaine A. Nelson is a professor of Art History and the Tier I Canada Research Chair in Transatlantic Black Diasporic Art and Community Engagement at NSCAD University in Halifax, Nova Scotia.

To lend your support to the Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery visit: https://nscad.ca/connect/give/support-the-institute-for-the-study-of-canadian-slavery/

For a schedule of Charmaine’s Black History Month lectures visit: https://nscad.ca/slavery-in-canada/

For more about Black Canadian Studies visit:

https://www.blackcanadianstudies.com/

For a schedule of Black History Month events in Halifax, NS and at NSCAD University visit: https://nscad.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/african_heritage_month_2021.pdf

Dr. Charmaine A. Nelson

Figure List

Fig. 1: John Turner, “FOURTEEN DOLLARS Reward,” Quebec Gazette, 11 March 1784, vol. 968, p. 3; Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BANQ), Montreal, Canada.

Fig. 2: James Crofton, “RUN-AWAY, from James Crofton,” Quebec Gazette, 14 May 1767, vol. 124, p. 4; Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BANQ), Montreal, Canada.

Fig. 3: Hugh Ritchie, “RAN-AWAY,” Quebec Gazette, 4 November 1779, vol. 740, p. 3; Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BANQ), Montreal, Canada.

Fig. 4: Simon Fraser, “ RUNAWAY from the ship Susannah,” Quebec Gazette, 30 September 1779, vol. 735, p. 3; Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BANQ), Montreal, Canada.

Fig. 5: Sarah Levy, “RUN away on the 11th Instant,” Quebec Gazette, 15 July 1768, vol. 185, p. 3; Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BANQ), Montreal, Canada.

Fig. 6: THE PRINTER (William Brown), “RANAWAY from the Printing-office,” Quebec Gazette, 27 November 1777, vol. 639, p. 3; Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BANQ), Montreal, Canada.

Fig. 7: Finlay and Gregory, “RAN AWAY on Saturday night,” Quebec Gazette, 21 May 1778, vol. 664, p. 3; Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BANQ), Montreal, Canada.

I had no idea. Thank you for providing this profound piece of Canadian history that has been patched-worked over. I have much to learn and unlearn.

Canada, as a country, has a lot of healing and growing to do. I believe it starts by giving a complete history, not a glossed over version. One that includes our shame and acknowledges our accountability and role in history. Thank you for the additional resources.

Incredibly informative. Thank you for sharing with us Dr. Nelson.

This is amazing. I didn’t know half of the information presented here and I am so happy to now learn about the Institute for the Study of Canadian Slavery to be able to learn more.

Thank you for sharing this enlightening essay by Dr. Nelson. I live in the U.S. and I am reminded how much I don’t know and how much I have to learn about the black diaspora in North America.